Artificial intelligence systems are increasingly making consequential decisions about our lives—determining who receives job interviews, loan approvals, or longer prison sentences. One might hope these algorithms would prove more objective than their human creators, but mounting evidence reveals that AI frequently perpetuates and amplifies existing societal biases, particularly along lines of race, gender, and socioeconomic status. The promise of objective, data-driven decision-making has collided rather spectacularly with the reality that AI systems trained on historical data inevitably absorb the prejudices embedded within that data—a discovery that surprised precisely nobody who’d ever opened a history book (O’Neil, 2016; Noble, 2018).

The mechanisms of algorithmic bias are often subtle and complex, which makes them both insidious and remarkably difficult to address. Machine learning models identify patterns in training data, and when that data reflects discriminatory past practices—such as biased hiring decisions or racially disparate policing—the algorithm dutifully learns to replicate those patterns with the efficiency only a computer could muster (Barocas and Selbst, 2016). A facial recognition system trained predominantly on white faces performs poorly on people of colour. A recruitment algorithm penalises CVs containing the word ‘women’s’, having learned from historical data that male candidates were more often hired—apparently the algorithm missed the memo about equal opportunities (Dastin, 2018). These biases can become entrenched at scale, affecting millions of decisions with minimal human oversight.

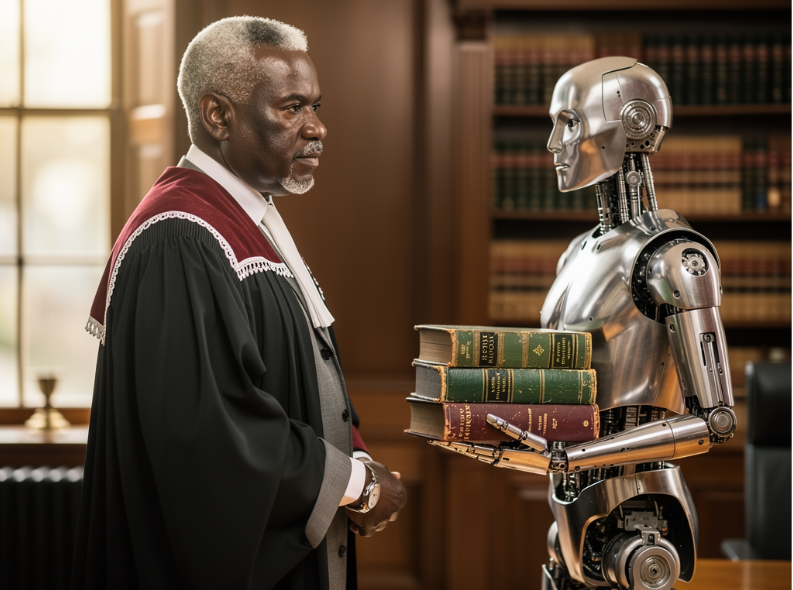

The stakes are particularly high in criminal justice applications, where the consequences of algorithmic bias extend far beyond inconvenience. Recidivism prediction tools used to inform bail, sentencing, and parole decisions have been shown to incorrectly flag Black defendants as high-risk at roughly twice the rate of white defendants (Angwin et al., 2016). Such systems claim scientific objectivity whilst encoding society’s existing inequalities into ostensibly neutral mathematical models—a feat of intellectual gymnastics that would be impressive if it weren’t so troubling. The result is a pernicious form of discrimination that carries the veneer of technical legitimacy, making it more difficult to challenge than overt human prejudice (Eubanks, 2018).

Addressing algorithmic bias requires multifaceted interventions throughout the AI development lifecycle. Technical approaches include auditing datasets for representational imbalances, employing fairness constraints during model training, and testing systems across demographic groups before deployment (Mehrabi et al., 2021). Yet technical fixes alone prove insufficient—rather like trying to solve a political problem with a calculator. Diverse development teams, transparency requirements, independent oversight, and mechanisms for affected individuals to contest automated decisions are equally crucial (Raji et al., 2020). Some jurisdictions are beginning to mandate algorithmic impact assessments for high-stakes applications, though whether these amount to genuine accountability or bureaucratic box-ticking remains to be seen.

Ultimately, algorithmic fairness is not merely a technical challenge but a profoundly societal one. We must grapple with fundamental questions about what fairness means in different contexts and whose values should guide AI systems (Binns, 2018). Should algorithms aim for equal treatment or equal outcomes? How do we balance efficiency gains against equity concerns? Can an algorithm be ‘fair’ when trained on data from an unfair society? These decisions cannot be delegated to engineers alone but require broad democratic deliberation—though getting humans to agree on fundamental values may prove more challenging than fixing the algorithms themselves. Unless we confront bias in AI systems head-on, we risk automating and legitimising the very discrimination that generations have fought to overcome (Benjamin, 2019).

References

Angwin, J. et al. (2016) ‘Machine bias’, ProPublica, 23 May. Available at: https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Barocas, S. and Selbst, A.D. (2016) ‘Big data’s disparate impact’, California Law Review, 104(3), pp. 671-732.

Benjamin, R. (2019) Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Binns, R. (2018) ‘Fairness in machine learning: Lessons from political philosophy’, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 81, pp. 149-159.

Dastin, J. (2018) ‘Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women’, Reuters, 10 October.

Eubanks, V. (2018) Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Mehrabi, N. et al. (2021) ‘A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning’, ACM Computing Surveys, 54(6), pp. 1-35.

Noble, S.U. (2018) Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press.

O’Neil, C. (2016) Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. London: Allen Lane.

Raji, I.D. et al. (2020) ‘Closing the AI accountability gap: Defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing’, in Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. Barcelona, Spain, pp. 33-44.